Your Lithograph Makes Me Look Fat: George Bellows and Reducing

February 24, 2012

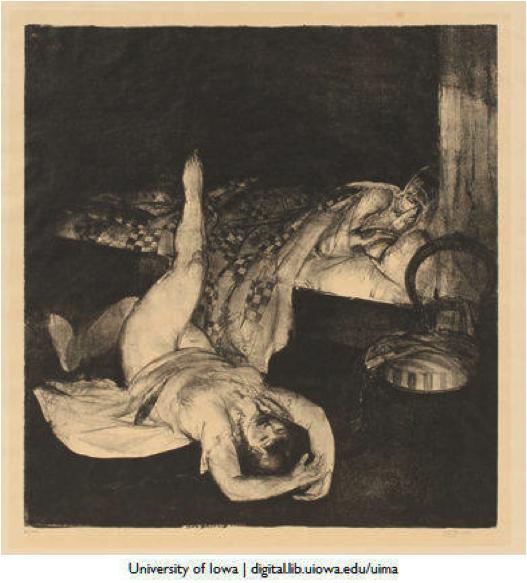

Princess Kate - See all 9 of my articles

In 1916, artist George Bellows produced this lithograph, the second of three in a series depicting women doing calisthenics while their husbands slumber peacefully unaware. Best know for his depictions of men’s lives in rough and tumble turn of the century America, these lithographs are a distinct departure for the artist, and represent his acknowledgment of the changes in store for women in the early 1900s. The woman depicted is forcing herself through exercises to meet the changing standard of beauty. The transformation in the ideal female figure from voluptuous to slim was as dramatic, and, for many women, challenging, as any other modification of modern 20th century life.

The Eternal Debate

A slender physique was often an available body ideal in Western culture, from the Aristotelian moderation of the Greeks to Christian ascetics whose revulsion of gluttony and the overweight came to America with the Puritans. However, until the last few decades of the nineteenth century, plumpness was largely the preferred physique for women. Full-figured women have a long tradition in Western art (Ruben’s chubby goddesses being perhaps the best known example of this), and the art of the nineteenth century largely maintained this tradition. Prominent nineteenth century stage actresses endorsed the popular body type by adding prominent bustles to their undergarments, adding boost to prominent derrieres to match the ample bosoms created by corsets. Women, especially those who had given birth, were supposed to be curvy. While thinness was seen as a sign of impending nervous disorders and general ill health, women with meat on their bones were linked to successful motherhood and genial good health.

An American Tale

This proclivity for plump figures, while fairly universal in the latter decades of the nineteenth century, had some overtones that were specifically American. America was a land of plenty, and the sheer size of their food and the large portions offered were drew frequent comments from foreigners. Visitors used to slight European portions at meals were stunned by the size of American game and produce, and the subsequently enormous meals that graced their plates. Women’s magazines like Godey’s Lady’s Book began publishing multiple recipe features in each issue, often concentrating on high-calorie offerings like cake. A single issue of the magazine could offer instructions on how to create pound cake, cream cake, chocolate cake, strawberry cake, and spice cake. Apparently the domestic prowess of American women was best expressed through fattening desserts.

One of the most influential illustrators of women in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century was Charles Dana Gibson, whose work could be seen in essentially every women’s magazine in America. His iconic “Gibson Girl” established a new standard of beauty that was distinctly modern and American. His illustrations of women, particularly famous for their high-piled hairdos, present fine-featured women notable for their tall and elegantly slender carriages. Whereas earlier fashion plates featured curvy busts and derrieres, the Gibson Girl was much more linear, her curves much less emphasized than in earlier depictions of idealized females.

Between 1895 and 1914, The Gibson Girl ideal was broadcast throughout America in a slew of prominent periodicals, illustrating to women what was expected of themselves and their bodies in the new century. Bellows was certainly aware of this new feminine ideal.

Loosen Your Corset

By 1914, the battle between the desirability of plump and slender silhouettes had been unanimously decided in favor of thinness. Beginning in the 1890s, fashion had begun to fall out of love with tightly corseted dresses and embrace a more natural look with fewer constrictions. As these modern fashions left the body to assume its own shape (and tended to be tighter-fitting than earlier clothing), a slender figure was required. As clothing production moved from hand-tailored to general manufacture, women with especially large figures often dresses in their size hard to find. In 1916, when Bellows created his Reducing print, women were dealing with constant societal pressure to be thin. Plump bodies were no longer seen as healthy, calm, and desirable, but lazy and gluttonous. A slender physique was emblematic of a whole host of moral and social virtues. The woman illustrated by Bellows is attempting to conform to this new national ideal.

If You Can’t Be Good, Be Thin

From where did this obsession with thinness come? From a purely medical point of view, the twentieth century saw cases of infant mortality and death from contagious diseases in a steep decline, and the population overall became more likely to live into old age. This allowed physicians to direct their research to degenerative, rather than infectious diseases, and the associated problems of the mature adult. With this emphasis on degenerative diseases came increased information about the correlation between weight and health issues. Extra weight, previously thought to shield man against nervous conditions and sickness (especially tuberculosis), now became associated with the causes of many illnesses like heart disease. In addition to strides in medical knowledge of obesity, the war between fat and thin began to take on strong moral overtones. American consumer culture was thriving in the first decades of the twentieth century, as department stores emerged, mail-order catalogs thrived, and manufactured goods became more and more accessible to all Americans. In the midst of this purchasing frenzy, many Americans worried that they were losing the moral fiber that came with Puritanical self-restraint. Middle-class Americans, concerned that they were losing their staunch religious character in the midst of a shopper’s paradise, turned to weight control as a substitute for religious fervor.

Although he will continue to be remembered for his evocative portrayals of the masculine, rough-and-tumble side of early twentieth century America, 1916’s Reducing proves that Bellows, husband and father of two daughters, recognized that times were changing for women, too. The dramatic transformation in the ideal female figure from voluptuous to slim was as important, and, for many women, challenging, as any other modification of modern 20th century life.

RSS

RSS